The Quaich

Remember the good old days? When life was simple, distillers were dodging the excise man, and people drank whisky out of an old boot? Well, probably not the latter, but with some of the Islays (like the amazing Lagavulins last Christmas), it might actually be interesting. And people have put their whisky in unlikelier vessels.

The classic drinking vessel for whisky is the quaich, which comes from the Gaelic cuach, meaning a cup or bowl. Today, one looks at quaichs with mixed emotions. They're beautiful, but - a little like the old boot - it is hard to imagine drinking whisky out of them. A good whisky glass tapers to a narrow opening, to enhance the aroma of the whisky. Connoisseurs (members of the Society all) know that the square-cut tumbler, or other "whisky" glasses with openings as wide as the body, are for the undiscerning only. Hence, when we see a quaich, which has the shape of a shallow bowl, we wonder what sort of whisky was drunk from it.

Nonetheless, quaichs have a rich heritage in Scotland - indeed, they are a uniquely Scottish invention, having no apparent connection to any other European drinking vessel. They were not only for whisky; larger quaichs were used for ale and other potables. The earliest written reference to quaichs dates from 1546, at which time they were already well-established in Scottish culture. The form and design of the traditional quaich became fixed during the "classic" period from 1660 to 1710. Through this time, most quaichs were made from wood; it was only later that silver quaichs became common.

The classic wooden quaich has the shape of a gently-sloped, shallow bowl. The sides taper toward the rim, giving the quaich a graceful, elegant appearance. Handles, called "lugs", extend from the sides, and these are often covered with silver. Most quaichs have two lugs, but some had three or even four lugs spaced around the edge.

Quaichmaking was a highly regarded profession in 17th century Scotland. Quaichmakers probably made all sorts of wooden eating and drinking vessels, but took the name of their profession from their best work, much as workers in silver and gold called themselves goldsmiths.

As with all things, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery. Quaichs became so highly regarded that the upper-crust just had to have them made from precious metals. This posed something of a problem, since wooden quaichs are solid and quite thick at the bottom - it would be a bit difficult for a fine Scottish lady to sip delicately from an solid silver ale quaich the weight of a small boulder. The answer was to make the quaich of sheet-silver, so that the sides were of constant thickness. This allowed metal quaichs to imitate the outer form of wooden quaichs, but made the inner cavity much deeper and more bowl-like.

The earliest quaichs were single-timber, meaning that they were made of a single piece of wood turned on a lathe. The lugs were sometimes covered with silver, providing a place for initials. It was a passion in 17th century Scotland to place your initials everywhere: on your silverware, your furniture, the lintel, ceiling, and panelling of your house, and - of course - on your quaich.

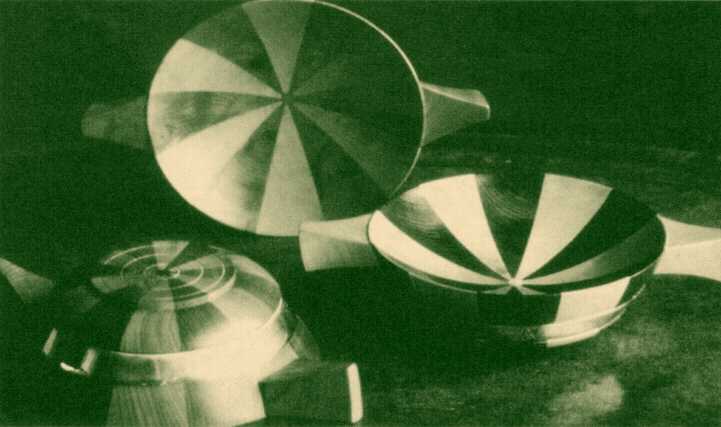

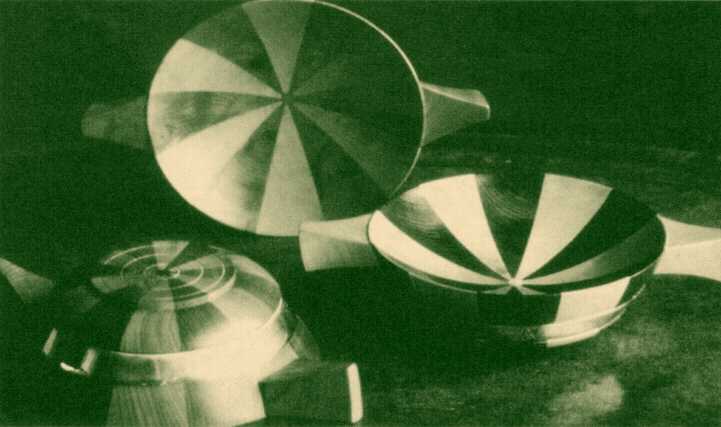

In the latter part of the 17th century came the stave-built quaich. The stave-built quaich is made of triangular staves of wood joined together at their points. The staves are made from different types of wood, of contrasting colours, to enhance the beauty of the finished quaich. Most quaichs have 10, 12, or 14 staves, though 16 was not uncommon, and one can occasionally find a quaich with an odd number of staves (perhaps from quaichmakers who had had one-too-many drams?). The staves may or may not be of uniform width, and each lug is a continuation of a single stave.

The staves meet in the centre of the quaich at a

small, round plug. The staves may either come together radially,

like a sunburst, or tangentially (as shown at right). Many times,

the staves were also "feathered" together. This is a

process where small slivers are cut and bent away from the side

of a stave, to fit matching cuts on the neighbouring stave (see

drawing). Usually two feathers join each pair of staves. Quaichs

are held together by the feathers (if present), and by strips of

willow (called withies) or silver bound around the outside of the

staves.

The staves meet in the centre of the quaich at a

small, round plug. The staves may either come together radially,

like a sunburst, or tangentially (as shown at right). Many times,

the staves were also "feathered" together. This is a

process where small slivers are cut and bent away from the side

of a stave, to fit matching cuts on the neighbouring stave (see

drawing). Usually two feathers join each pair of staves. Quaichs

are held together by the feathers (if present), and by strips of

willow (called withies) or silver bound around the outside of the

staves.

I first got to know quaichs through an exhibition at

the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. The exhibition

showed the history of quaichs and included some amazing

modern-day reproductions. The reproductions were built by Richard

Brockbank, a woodworker and artist who became interested in the

challenge of accurately recreating classic wooden quaichs.

According to the National Museum, his quaichs "capture,

absolutely, the proportions and essence of the originals".

Not being a historical expert, I can only say that they're

beautiful to look at.

I first got to know quaichs through an exhibition at

the National Museum of Scotland in Edinburgh. The exhibition

showed the history of quaichs and included some amazing

modern-day reproductions. The reproductions were built by Richard

Brockbank, a woodworker and artist who became interested in the

challenge of accurately recreating classic wooden quaichs.

According to the National Museum, his quaichs "capture,

absolutely, the proportions and essence of the originals".

Not being a historical expert, I can only say that they're

beautiful to look at.

Mr. Brockbank has reproduced two types of quaich: single-timber quaichs, and stave-built quaichs with 12 staves of equal size. He uses a wide variety of native Scottish woods, including laburnum, cherry, apple, yew, and burr elm.

He also reproduced feathering, although this proved to be very challenging. It requires the staves to be roughly shaped before assembly, so that the feathers can be accurately cut. The quaich is then assembled and finished on the lathe. Additionally, half of the feathers have to be cut against the grain, which is difficult with harder woods.

Quaichs are still being made today, mostly as prizes for sporting events or as objets d'art. However, most modern quaichs pay only passing attention to the classical form. It is refreshing to find a modern craftsman reproducing the classic quaichs of the 17th century. While quaichs are no longer used as drinking vessels, except perhaps at weddings or other ceremonial occasions, they are beautiful examples historical craftsmanship and items of uniquely Scottish heritage.

Bradley Richards

If you're a lover of tradition, you could do worse than to commission a quaich of your own; the cost ranges from £200 to £300. If you come by the Society offices in Switzerland, we'll be happy to show you the quaichs that we commissioned after seeing the exhibition at the National Museum. Or contact Mr Brockbank directly: Mr. Richard Brockbank, Bay Cottage, Findhorn, Moray IV36 OYY, Scotland, UK.

Unless otherwise noted, all information in this site © The Scotch Malt Whisky Society, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1997.