Somewhere near the ancient Perthshire village of Doune, you take a B-road. Then an even narrower B-road. Then on the edge of the chattering waters of the River Teith, you discover an 18th century cotton mill.

It is undeniably a cotton mill. The size and the stately proportions proclaim it as such, although you'd be hard-put to find a cotton mill still operating in Scotland. Yet all the signs, from the buzz of industry to the plume of steam, tells you that this place is still in business. The secret lies inside.

This is a cotton mill that became a malt whisky distillery, and did so with great alacrity, as if it was discovering its higher role in the world. All the facilities were there: plentiful water for power, which was also soft water for whisky-making, a sylvan setting, an optimistic climate in the distilling industry when the transformation came about in the mid-Sixties.

The malt is called Deanston, and Society members (who have sipped it enthusiastically as No. 79) will not be unfamiliar with the name. But, with the conventional picture of a malt whisky distillery in their minds, they could hardly imagine its birthplace.

So first, let us go back to 1785. That is when the cotton mill came into being, to be described in The First Statistical Account of Scotland as having 'the most perfect machinery in the kingdom'. The owners were four brothers, one of whom was associated with Sir Richard Arkwright, English inventor of the water-powered spinning frame.

But here's an interesting touch. 'The English had annoyed Sir Richard so much by invading his invention he resolved to instruct young Scotsmen in the art, in preference to his own countrymen.' Oh dear.

The mill passed through several hands until it ceased production in 1965. So then, an enormous complex with vast storage space came on the market and attracted the interest of Brodie Hepburn Ltd, at that time the company operating the nearby Tullibardine Distillery. It seemed ideal for warehousing. But when they inspected it (and remember, these were highly optimistic times) their minds turned inevitably to a new distillery.

The waters of the Teith were analysed. Flowing from feeder streams high in the Trossachs, filtered through granite and running over peat beds, this stuff was far too good for the cotton business. Not only that, but the river gave the mill its own power supply through two turbines, one of which has been working faithfully since the mid-Twenties. Incredibly, this set-up produced so much juice that it could sell the surplus to the national grid.

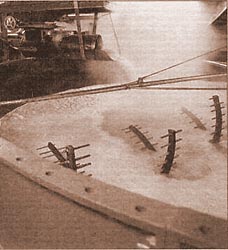

The water-power is conducted to the turbines from a 1.5 mile man-made lade, later returning to the river through a 300-metre tunnel of splendid arched masonry. The water arrives at two huge cast-iron flumes which once fed four gigantic overshot wheels, each rated at 80 horse-power: a gem of the Industrial Revolution now adapted to a later century.

In partnership with the mill-owners, Brodie Hepburn plunged so enthusiastically into the conversion work that this superb cotton mill started producing its first malt whisky only 10 months after the deal was agreed. The first drams were bottled as a five or six-year-old single called 'Old Bannockburn' and put into a blend named 'Teith Mill'

The strategy of the new company,

Deanston Distillers Ltd, was to buy an established blend

brand-name and use their malt as the basis. This didn't happen,

and in 1972 both Deanston and Tullibardine distilleries became

part of Invergordon Distillers. In 1982, Deanston was mothballed.

The strategy of the new company,

Deanston Distillers Ltd, was to buy an established blend

brand-name and use their malt as the basis. This didn't happen,

and in 1972 both Deanston and Tullibardine distilleries became

part of Invergordon Distillers. In 1982, Deanston was mothballed.

Now we come to the story of Deanston as it is today. In 1990 the distillery was bought by Burn Stewart, the Glasgow company of blenders and bottlers ambitious to expand into distilling. (These ambitions were underlined in July this year when the company bought the faltering Ledaig Distillery on the Isle of Mull.)

Deanston's new manager Ian Macmillan, was one of the first to inspect the new acquisition beside the Teith. The mothballed distillery, hidden inside the cotton mill, was complete all right: but there were archaic parts of the operation that had to be improved.

One was the system for filling the eight 60,000 litre washbacks. The worts were pumped in from above through a single dismountable pipe of copper and plastic, rather like a garden hose. So a first job was to install permanent stainless-steel pipes and valves, to fill the washbacks in a more efficient and dignified fashion, incorporating an in-house cleaning system.

But there was much about the

quarter-century-old fittings that gave pleasure. From the four

25-tonne malt bins, the barley is conveyed to an unusually

elegant wooden-panelled room where the 1966 Porteous mill grinds

away in some state. The elevators that convey the grist, and the

equipment for extracting dust and pebbles, are neatly encased in

wood.

But there was much about the

quarter-century-old fittings that gave pleasure. From the four

25-tonne malt bins, the barley is conveyed to an unusually

elegant wooden-panelled room where the 1966 Porteous mill grinds

away in some state. The elevators that convey the grist, and the

equipment for extracting dust and pebbles, are neatly encased in

wood.

The enormous cast-iron mash tun, open-topped and with a false bottom of brass plates, is a high-quality piece of engineering made by an Alloa foundry that no longer exists. Newly refurbished, it is equipped with a mechanical mixing-rake, circling on a track of fixed cogs. Ian MacMillan finds its gentle mixing action superior to the blades of the more modern Lauter tun: it produces a dark, clear, unclouded wort, free of solids.

Deanston's two pairs of stills (by Archbd McMillan and Co, Prestonpans) are large and bulbous but also high. Unusually, the lyne arms from the swan neck to the condensers are set at a slight upward angle, aiding the reflux action which give a purer spirit.

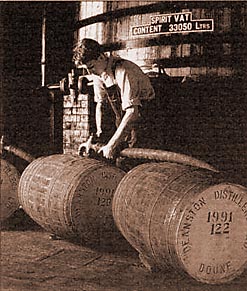

One of the maturing warehouses is

beautiful beyond description, a former weaving shed from 1785 of

arched stone roofing that would bring a hush to a chateau in

Burgundy. Here and in more modern racks, the distillery can store

45,000 casks, and the oldest Deanston they hold is the 1967.

One of the maturing warehouses is

beautiful beyond description, a former weaving shed from 1785 of

arched stone roofing that would bring a hush to a chateau in

Burgundy. Here and in more modern racks, the distillery can store

45,000 casks, and the oldest Deanston they hold is the 1967.

But of course, the whisky stocks they took over were of somebody else's distillation. It will be the next millennium before we taste the Deanston presided over by Ian MacMillan. What will it be like? 'Even better,' he said (and he has been checking on its progress).

His aim and that of production director Billy Walker, after months of initial experimentation, is to use only the residual peaty phenols of the Teith's soft waters and to mash with unpeated malt from Angus, East Lothian and Moray. 'The result will be a lightly-peated sweet whisky with the flavour of the malt dominant.'

An eighth of Deanston's new production, matured in whisky and bourbon refill casks and possibly with no sherry-cask whisky involved, will be bottled as the single, maybe from the year 2000. So...patience, friends.