The red brick chimney is the give-away. A self-effacing sort of a chimney that protrudes from a hollow in the prosperous East Lothian countryside. A brickworks perhaps? A distillery would not be your first thought. Unless, that is, you are one of Glenkinchie's dedicated admirers, on a pilgrimage to Pentcaitland.

This is not the rocky landscape of smuggler's caves and remote mountain passes, of rushing rivers running black with peat - all that makes up the romance and the legend of uisge beatha.

Only 15 miles from the centre of Edinburgh, this is decent, well-tended farmland with neat hedges, neat houses and a few neat bank-balances. A bit short on magic and mystery, but representative of virtuous men who knew what they were doing and did it well.

This is the kingdom of Lot, brother-in-law of King Arthur, from whom Lothian takes its name. He held court on the summit of Traprain Law, not far from Glenkinchie. The land here has been under plough for 2000 years and they grow some the best barley in Britain.

No less a countryman than Robert Burns described it as "the most glorious corn country I have ever seen". No less a countryman than John Cockburn lived in the next village to Pentcaitland. Known as the "Father of Scottish Husbandry", in the early 18th century he founded the Society of Improvers of Knowledge of Agriculture.

This worthy title doesn't do justice to the revolutionary genius of the man who introduced farming methods that put East Lothian ahead of the world. He also introduced the potato and the turnip to Scotland - thus inventing the Burns Supper!

It is impossible to be certain when whisky was first produced in East Lothian. The first written record is a royal command of 1494 but by then the practice was already widespread. Distilling was an intrinsic part of the farming cycle. An obvious means of turning barley into cash. The spent grain was then used to fatten cattle.

However, after the Union of Scotland and England the tax on whisky, which had existed more or less theoretically since 1655, was now enforced. Not only were the excise men demanding duty on something the farmers saw as being as natural as the seasons themselves, but they were doing it in the name of England! Battle was joined.

Illicit distilling in the Lothians went on its merry way. Seventy years after the implementation of the tax, in 1777, there were only eight licensed stills in nearby Edinburgh. Four hundred illicit ones were discovered.

In 1837, a licence to operate a

distillery at Glenkinchie was granted to pair of local farmers,

the brothers George and John Rate. They are known to have owned a

distillery in the area called Milton from 1825 and it seems

likely that Glenkinchie was the same business trading under a new

name.

In 1837, a licence to operate a

distillery at Glenkinchie was granted to pair of local farmers,

the brothers George and John Rate. They are known to have owned a

distillery in the area called Milton from 1825 and it seems

likely that Glenkinchie was the same business trading under a new

name.

Glenkinchie was a model of self-sufficiency. The brothers grew the barley and malted it. They drew water from the Kinchie Burn (Kinchie is a corruption of the Norman name de Quincey, a family which once owned the surrounding land) and mashed it to make malt whisky. Cattle and horses flourished on the "draff".

This relationship between the distillery and the land at Glenkinchie has remained unbroken, although nowadays it hangs on by a thread. The 85-acre farm is still there but leased out, although for many years a distillery manager, W J McPherson, farmed the land himself, making Glenkinchie famous for its Aberdeen Angus cattle.

The mighty Clydesdales have gone but Hector MacDonald, one of the still operators, worked the horses as a boy as did his brother and their father before them. The dray horses' job was to cart the whisky casks to Saltoun railway station about a mile away, rattling over the little stone hump-back bridge which is still a prominent feature. They would come back loaded with barley or coal for the furnaces. The drays that Mr MacDonald thought to have a suitable temperament for city life went away to Glasgow, to Buchanan's bonded warehouses. But they came back to the green fields of Glenkinchie for their summer holidays.

The casks go out by lorry now, to mature in a huge modern complex in Alloa. The three Glenkinchie warehouses are full. The malt comes in by lorry, from Roseisle in Morayshire, already prepared to the distillery's lightly peated "recipe".

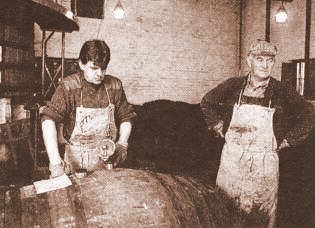

Hector MacDonald (a stillman who's never touched a drop of whisky in his life) remembers taking a tin mug to school with him to scoop up the pure malt from the malt house floor ... he smiled contentedly at the memory. The maltings closed in 1968 and the malting floor was converted into museum - the only museum of malt whisky production in the world and the brainchild of the then manager, Alistair Munro.

The closure of the maltings floor brought home to him how rapidly the industry was changing and he determined to record the memories and the machinery. This year should see the opening of an important new visitors' centre.

The whole feel of Glenkinchie is very Victorian. In 1890 the Edinburgh consortium who took it over from the Rate brothers completely restructured the distillery and gave it the "Bourneville" treatment, building a small village of houses for the workers and supplying them with fresh food from the farm. Later, in the 1920s, the workers laid out a bowling green which is still well tended. Only a handful of the cottages remain in the distillery's ownership, although some families bought theirs and still live there.

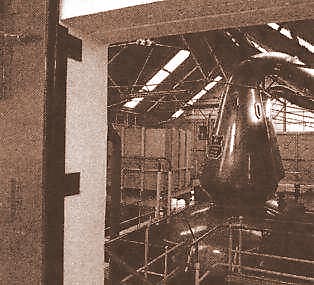

In 1972 the still house was rebuilt and

the stills were converted to internal coil heating. In 1995 a new

mash house was built. But it has all been done with care and a

gentle touch. The six wooden washbacks remain: two made from

Oregon pine and four from Canadian larch. There are two copper

pot stills for distillations and the wash still, with its

capacity of 32,000 litres, is one of the largest in the industry.

It shares with the spirit still a traditional worm condenser,

coiled two stories high.

In 1972 the still house was rebuilt and

the stills were converted to internal coil heating. In 1995 a new

mash house was built. But it has all been done with care and a

gentle touch. The six wooden washbacks remain: two made from

Oregon pine and four from Canadian larch. There are two copper

pot stills for distillations and the wash still, with its

capacity of 32,000 litres, is one of the largest in the industry.

It shares with the spirit still a traditional worm condenser,

coiled two stories high.

One thing is constant: the water that is drawn from the Kinchie Burn. Diamond bright and diamond hard, it rises in the Lammermuir Hills, running over rich limestone deposits. And the chalk makes Glenkinchie the driest of all the Lowland malts.

It is this water and the climate - sunnier and drier than the Highlands - which gives Glenkinchie and the other Lowlanders their quite distinct character. Lighter and drier than their Highland and Island cousins, the soft sweetness of the malt is allowed to come through.

This very versatile style of whisky appeals to the Lowland palate and makes it beloved of the blenders. (Glenkinchie is a component of - among others- Haig Dimple). By the 1890s blended whisky was being sold in 120 countries, with Edinburgh and its Port of Leith at the hub of the trade.

As Edinburgh prospered and grew, so did the distillery at Glenkinchie, but now in the ownership of an Edinburgh consortium of brewers and wine merchants. In 1914 the company they established was one of five Lowland malt whisky distilleries to form Scottish Malt Distillers, now part of United Distilleries.

Now this soft, restrained whisky takes its place as the Lowlands representative in the United Distillers' Classic Malts range, marketed as "The Edinburgh Malt." Its output currently runs at full capacity and the opening of the new visitors' centre later this year is expected to draw in about 60,000 visitors per annum once it is up and running. This modest little distillery must be blushing red to its Victorian brick.

Gillian Strickland

Unless otherwise noted, all information in this site © The Scotch Malt Whisky Society, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1997.