Reading Barnard immediately after a

visit to Laphroaig distillery, one is struck by how much remains

as it was when the Baedeker of Scotch whisky visited it in 1886.

The means may have been different - a ridiculously small aircraft

of the elastic band variety, apparently held together by rivets,

as opposed to Barnard's boat, and a bus where he had a horse and

cart - but the end is much the same. The distillery is of very

old-fashioned type, lying in a hollow by a little bay. The beach

where the puffers pulled up to unload coals is still suitable for

small steamers, the pretty little burn still brawls through the

policies and the view across the Sound of Jura to the Isle of

Gigha and the Kintyre coast has changed not at all.

Reading Barnard immediately after a

visit to Laphroaig distillery, one is struck by how much remains

as it was when the Baedeker of Scotch whisky visited it in 1886.

The means may have been different - a ridiculously small aircraft

of the elastic band variety, apparently held together by rivets,

as opposed to Barnard's boat, and a bus where he had a horse and

cart - but the end is much the same. The distillery is of very

old-fashioned type, lying in a hollow by a little bay. The beach

where the puffers pulled up to unload coals is still suitable for

small steamers, the pretty little burn still brawls through the

policies and the view across the Sound of Jura to the Isle of

Gigha and the Kintyre coast has changed not at all.

Perhaps the visitors have, somewhat. We had a contingent of Japanese whose visit, it seems, was a reward for sales achievement. If ever I am to be marooned on a desert isle with a bunch of salesmen, I sincerely hope it will be with Japanese.

Their natural courtesy and intelligence, as well as their good humour, would make it a pleasure. Having over the last year spent a fair bit of time in Japan and in Hebrides, I can see a few reasons why there seems to be a natural affinity between the Japanese and the Scots. Besides a liking for whisky, there are strong cultural affinities, standards of behaviour and systems of belief.

The Islay people, say Barnard, are very

hospitable. Then as now. Laphroaig is not one of those outfits

which lie like litter on the whisky trail, traps for tourists,

painted and neat so that busloads of geriatrics will commend them

for their tidiness. It is a working distillery and looks it,

though clean enough for any granny. It doesn't turn tourists away

but it does not cater for busloads of the terminally bored

either. If you want to see it, you must ring first and arrange to

visit - not a great disincentive. The return for such a small

effort is disproportionately great, for there is a strong

likelihood that you will be shown round by the admirable Iain

Henderson himself, the distillery manager. He is a big

improvement on the lassies in blazers and kilts that you get at

the showbiz end of the whisky business.

The Islay people, say Barnard, are very

hospitable. Then as now. Laphroaig is not one of those outfits

which lie like litter on the whisky trail, traps for tourists,

painted and neat so that busloads of geriatrics will commend them

for their tidiness. It is a working distillery and looks it,

though clean enough for any granny. It doesn't turn tourists away

but it does not cater for busloads of the terminally bored

either. If you want to see it, you must ring first and arrange to

visit - not a great disincentive. The return for such a small

effort is disproportionately great, for there is a strong

likelihood that you will be shown round by the admirable Iain

Henderson himself, the distillery manager. He is a big

improvement on the lassies in blazers and kilts that you get at

the showbiz end of the whisky business.

Iain describes how he first came to know Laphroaig. As a young man in the 1950's - he is not so old now, so he must have been very young then - he was the engineer on a British merchant ship, sharing a piece of the Indian ocean with a hurricane. The crew having adopted drams as a prophylactic against irregular motion, whisky stocks ran out before the hurricane did, so crew were forced back onto the chief steward's stock of Laphroaig. This, the product of some shady barter arrangement, lasted long enough for the young Henderson to acquire the taste.

This story is told because there seems

to be some lesson in it. Quite what that is, is not immediately

apparent, but it may become so as the Laphroaig goes down. There

can be no doubt, it is an acquired taste. You either love it or

you hate it; few are indifferent. Even those who dislike the

stuff will generally admit that there is a very fine whisky under

the peat reek.

This story is told because there seems

to be some lesson in it. Quite what that is, is not immediately

apparent, but it may become so as the Laphroaig goes down. There

can be no doubt, it is an acquired taste. You either love it or

you hate it; few are indifferent. Even those who dislike the

stuff will generally admit that there is a very fine whisky under

the peat reek.

The latter is the main reason for the very distinctive nose and taste. The distillery malts a large part of its own barley and on almost any working day, the distillery can be found by nose alone, if you happen to be downwind. It has a proper malthouse with several floors where the barley is malted in the traditional manner and a kiln where it is dried. The kiln has proper pagoda roofs and altogether the whole thing looks and smells as it ought. The malt, once dried, is sweet, crisp and incredibly smoky.

There is a widespread belief that the

peculiar flavour of Islay malts is caused by their littoral

location, hence descriptions of them as being seaweedy and full

of iodine. While the influence of the sea cannot be discounted

entirely, it must be negligible by comparison with the effect of

the peatsmoke from the malt kiln. Certainly, when Barnard asked

the then distillery owner, the latter was quite clear that it was

the peat that mattered. It would be interesting to see a highland

whisky made from heavily-peated malt. The nearest we have is

probably Clynelish, which could easily be mistaken for an Islay,

for it has a more peaty nose than some of the Islays, such as

Bunnahabhain or Bruichladdich, which use lightly-peated malt.

There is a widespread belief that the

peculiar flavour of Islay malts is caused by their littoral

location, hence descriptions of them as being seaweedy and full

of iodine. While the influence of the sea cannot be discounted

entirely, it must be negligible by comparison with the effect of

the peatsmoke from the malt kiln. Certainly, when Barnard asked

the then distillery owner, the latter was quite clear that it was

the peat that mattered. It would be interesting to see a highland

whisky made from heavily-peated malt. The nearest we have is

probably Clynelish, which could easily be mistaken for an Islay,

for it has a more peaty nose than some of the Islays, such as

Bunnahabhain or Bruichladdich, which use lightly-peated malt.

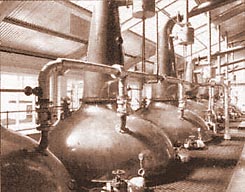

Besides the malthouse at Laphroaig, the distillery has the usual complement of mashtuns, washback, stills, etcetera. There are six stills, of the swanneck variety. The process of shifting spirit from one still to another is a complex one, requiring fine judgment on the part of the stillman. Iain explained that though this, like much of the rest of the distillery, is fairly old-fashioned, the owners see no reason to change it, on the very good ground that since the present kit makes some of the best liquor on the planet, change is unlikely to be for the better.

The distillery guards its water supply

most carefully. It owns all of the land from which flows the burn

which supplies the mashtuns. There are no cows or sheep on the

moor, or any human intrusion, so that the distiller may be sure

that all of the influences on the water supply are as natural as

possible. It appears that the greatest care has been taken of the

quality of the materials from a very early date.

The distillery guards its water supply

most carefully. It owns all of the land from which flows the burn

which supplies the mashtuns. There are no cows or sheep on the

moor, or any human intrusion, so that the distiller may be sure

that all of the influences on the water supply are as natural as

possible. It appears that the greatest care has been taken of the

quality of the materials from a very early date.

The distillery had for many years the distinction of being the only Scotch malt distillery owned and run by a woman. Bessie Williamson joined the company in the 1930's as a chemist. She rapidly came to take control of the production process and in the early 1950's became owner. She continued to run the business and the distillery until the 1960's. Her expertise in and love for her product is sufficient evidence, if any were needed, of the falsity of the macho image of Scotch whisky in general and Islays in particular.

The Laphroaig is matured at the distillery in American bourbon casks. In the warehouse, the Kentucky origins are sometimes evident on the cask ends, which bear stencils of Jim Beam and Jack Daniels. The proprietary bottlings of Laphroaig are at ten and fifteen years old, all from bourbon casks.

Laphroaig is the market leader for Islay

malts, and may take most of the credit for the prominence of

whiskies from that island in world markets. Annual sales are an

astonishing 80,000 cases of the stuff, which just to show that if

you have a taste for tar, you are not alone.

Laphroaig is the market leader for Islay

malts, and may take most of the credit for the prominence of

whiskies from that island in world markets. Annual sales are an

astonishing 80,000 cases of the stuff, which just to show that if

you have a taste for tar, you are not alone.

There are two proprietary bottlings: a ten year old and a fifteen year old. Both are excellent, though it was the opinion to the Committee that the spirit benefited from the additional five years' maturation, the older whisky undoubtedly being the better of the two. The comparison of ten year old, fifteen year old and Society bottlings (of 18 year old) is instructive. Laphroaig use only bourbon casks for maturing their spirit. There are sherry butts in the warehouse, but these belong to customers who require such maturation for their blends. The bourbon is all in American white oak. There is some variation among casks, but as far as we could see, not a lot. The result is a pretty consistent maturation, from which the effect of age is particularly apparent.

As most members should know, age in cask beyond about ten years is not necessarily a good thing in a malt, though many casks do continue to improve beyond that point. In the case of Laphroaig and its bourbon casks, the process appears to be fairly consistent, with the older whiskies being the more appealing in some ways, less in others. We realise that statistically this is a small sample and hence generalisations may be invalid. However, the consistent quality of the casks which we inspected gives us confidence in the general proposition. Having said that, we are all agreed that the combination of bourbon wood with heavily-peated malt is a most felicitous one.

Unless otherwise noted, all information in this site © The Scotch Malt Whisky Society, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1997.