Oban

Distilling wisdom under the folly

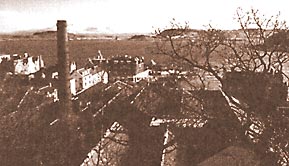

The first glimpse of Oban is spectacular, no matter how you

approach the town. From the North, the A85 descends through a

cleft in the ridge and, as it winds down the hill, the town with

its bay spreads out below. The railway is no less dramatic, for

it emerges from a cutting suddenly into the middle of the town,

and the trains come to a halt a few paces from the shore. But the

best approach is from the sea, by way of Kerrera Sound or, from

the North, by Dunollie Castle on the point. Then the town appears

as a semi-circle; an amphitheatre whose terraces are streets of

grey Victorian villas backing onto a cliff surmounted,

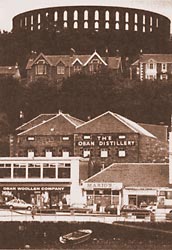

improbably, by what appears to be a minor Coliseum. Although this is the principal entrepot of the West Highlands,

it is important to grasp the scale of the town. From MacCaig's

Folly (the Coliseum affair) the cliff falls seventy feet or so,

and to walk in a straight line from its foot to the shore will

take you all of three minutes. Between cliff and strand are a sea

wall, a road, some shops and a distillery. The distillery is a range of fine, warehouse-like buildings

surmounted by an iron-banded chimney. The buildings are of grey

granite like the villas, and they are subject to what seems a

local obsession with architectural form, for the surrounds of

windows and doors all are painted, as if in emphasis of their

function. The chimney is red brick, painted red. The water for the whisky comes from a loch in the hills behind

the town. The name of the loch is easy to say but, in the true

tradition of Gaelic orthography, almost impossible to spell. The

malt, which is lightly-peated, is not made locally, but is

delivered by truck from a central maltings. It is steeped in a

stainless steel mashtun and fermented in four wooden washbacks:

vessels which, like the whisky casks themselves, are made by a

cooper and depend for their impermeability solely upon the fit of

stave against stave. The staves are twenty feet long. The still house is tiny: a wash still and a spirit still

proceed at a leisurely pace in a finely-balanced distillation.

Both are swan-necked and the spirit still has a lye pipe which

bends at a curious angle as it passes through the wall to the

worm condenser - which is not a worm at all, but a series of

copper pipes which run back and forth, the length of a stainless

steel tank. They do not look like a worm, but they do the work of

one, and Ian Williams, the manager and distiller, explains that

the bent pipe and the stretched worm are only two of the

individual features whose influences combine to produce a

highly-distinctive distillate. This is worth mentioning, for large distillery groups often

take stick for actions which appear to reflect the short-termism

typical of so much of British industry. In fact, the whisky

industry has always had long perspectives: they are intrinsic to

a product which needs ten years between production and sale.

Nonetheless, it is good to be able to report that United

distillers, the proprietors of Oban distillery, appear to be well

aware that the individuality of the distillery is essential to

the character of the malt, and are prepared to sacrifice profit

in the long-term interest of quality and identity. It is a view which will support both tradition and innovation.

When the mashhouse needed to be rebuilt, Ian asked that it be

kept traditional: no automation, no computers, just the attention

of a conscientious mashman. This was duly done. On the other

hand, when he sought to respond to the growing demand for

distillery tours, he was able to convert the old filling store

into a highly-successful visitors' centre. Its tableau of

caveperson eating fish is a useful illustration of the advance in

table manners since the upper mesolithic, but a bit over the top

as an introduction to whisky. That apart, however, the whole

thing is well done and the punters love it. Ian's assurance on matters to do with his distillery is

balanced by a becoming modesty in most other things. It is a

characteristic which has universal appeal and no doubt is a

factor in the demand abroad for his services as one of UD's brand

ambassadors. A Scottish distillery manager is the genuine article

and is regarded as an exotic in places like Japan and America,

hence the proliferation of requests for Ian's presence. It is not

uncommon for such celebrity to go to the head and it is pleasing

to be able to report that Ian Williams seems to be largely

immune. He rations his overseas visits quite severely, arguing

that his value and his authenticity lie in his being the manager

of Oban distillery, and that he can't claim to be that if he is

all the time traipsing off to foreign lands. Phillip Hills Unless otherwise noted, all information in this site © The Scotch Malt Whisky Society, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1997. It is a very urban distillery; economically,

spiritually and geographically. If the bay were a lamp, its light

would be the distillery and the island of Kerrera the focus of

its illumination. About two centuries ago, distillery and town

were founded by the Stevensons, a family of entrepreneurs of

startling ambition and energy. The present distillery offices are

housed in their former residence. The distillery is one of the

largest employers in the town and the distilling staff are the

aristocracy of local labour.

It is a very urban distillery; economically,

spiritually and geographically. If the bay were a lamp, its light

would be the distillery and the island of Kerrera the focus of

its illumination. About two centuries ago, distillery and town

were founded by the Stevensons, a family of entrepreneurs of

startling ambition and energy. The present distillery offices are

housed in their former residence. The distillery is one of the

largest employers in the town and the distilling staff are the

aristocracy of local labour.

Not least among those influences is Ian himself. A

tall, fair Aberdonian, he has worked in the whisky industry since

shortly after leaving school and has been at Oban as manager

since 1983. Two things are immediately evident: his total

dedication to his distillery and his confidence in his company.

The latter is well-justified, for Ian has found ready support in

the upper echelons of the company for his determination that

every idiosyncrasy of the distillery be preserved, despite the

continuing cost of doing so.

Not least among those influences is Ian himself. A

tall, fair Aberdonian, he has worked in the whisky industry since

shortly after leaving school and has been at Oban as manager

since 1983. Two things are immediately evident: his total

dedication to his distillery and his confidence in his company.

The latter is well-justified, for Ian has found ready support in

the upper echelons of the company for his determination that

every idiosyncrasy of the distillery be preserved, despite the

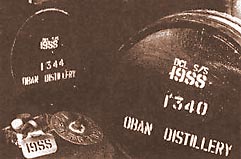

continuing cost of doing so.  They love the whisky too, and with reason, for it is

good stuff. It is matured in refill casks for fourteen years and

the result is an excellent dram of considerable character. One's

only grouse, from a Society point of view, is as regards the

casks. These are supplied by the parent company's cooperages.

They are well-chosen to ensure a consistent maturation of high

quality - but of course their very consistency leaves little

scope for the kind of variation which we in the Society are

normally able to exploit. Ian Williams is in no doubt: this is

the best sort of cask for the maturation of his spirit. It would

be churlish to disagree with such conviction.

They love the whisky too, and with reason, for it is

good stuff. It is matured in refill casks for fourteen years and

the result is an excellent dram of considerable character. One's

only grouse, from a Society point of view, is as regards the

casks. These are supplied by the parent company's cooperages.

They are well-chosen to ensure a consistent maturation of high

quality - but of course their very consistency leaves little

scope for the kind of variation which we in the Society are

normally able to exploit. Ian Williams is in no doubt: this is

the best sort of cask for the maturation of his spirit. It would

be churlish to disagree with such conviction.