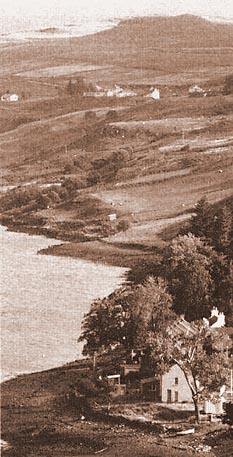

Sit in the manager's office of Talisker Distillery

at Carbost and watch the sun move slowly across the steep shore

of Loch Harport, and it's not too difficult to understand some of

the reasons for the existence of this most unlikely of

distilleries. For as the sun moves it picks out the lines of

lazy-beds that lie almost all the way along this apparently most

inhospitable lochside. And, if you drive from Carbost onto the

main road at Glendrynoch, the fast-moving late-afternoon light

catches more forgotten strips of intensively cultivated land

around the head of the loch. These long-discarded remains of a

thriving, if not hard-fought, agricultural economy are testimony

to the purpose of the man who founded Talisker Distillery, and to

the work of many more whose lives, and whose family's lives, were

prey to Hugh MacAskill and the inexorable economic and social

forces that shaped his ambition, and the ambitions of many others

like him in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Sit in the manager's office of Talisker Distillery

at Carbost and watch the sun move slowly across the steep shore

of Loch Harport, and it's not too difficult to understand some of

the reasons for the existence of this most unlikely of

distilleries. For as the sun moves it picks out the lines of

lazy-beds that lie almost all the way along this apparently most

inhospitable lochside. And, if you drive from Carbost onto the

main road at Glendrynoch, the fast-moving late-afternoon light

catches more forgotten strips of intensively cultivated land

around the head of the loch. These long-discarded remains of a

thriving, if not hard-fought, agricultural economy are testimony

to the purpose of the man who founded Talisker Distillery, and to

the work of many more whose lives, and whose family's lives, were

prey to Hugh MacAskill and the inexorable economic and social

forces that shaped his ambition, and the ambitions of many others

like him in the first half of the nineteenth century.

Retrace your steps. Drive back towards Carbost, but at the head of the steep and narrow road that leads down into the village turn left and pass the waterfalls of Carbost Burn. It never seems possible that this vigorous stream that provides the cooling water for the large worm tubs at the back of Talisker's still-house runs dry, but as manager Mike Copeland discovers every summer, it does. Stereotype Skye weather, like its people, at your peril! As you follow the steep road through Gleann Oraid, Talisker River rushes to your left, and then to your right, descending steeply to run into the sea at the steep cliff-sided Talisker Bay. And here, almost in breathless isolation sits Talisker House, whose timeless tranquillity belies the restless energy of the water that hustles past it, the savagery of the nearby mountains and the ruthlessness of some of its occupants, most notably our distillery founder, Hugh MacAskill.

To do him credit, MacAskill was not the first to clear the land at Talisker. Donald Macleod had let the estate to Lauchlan MacLean in 1818, and it was then that the process of moving people from the bulk of the land to displace them with more profitable sheep was begun. MacAskill, then, only completed the work, taking over Talisker estate in 1825. The distillery was a key part of his strategy. It would provide employment for those who remained on the land, and also a market for the barley produced on the diminishing areas of land that were set aside for arable cultivation. Built in 1830 at Carbost, one of the communities on the shores of Loch Harport that he had largely cleared of families, the distillery was described by a former minister of the Parish as "one of the greatest curses that, in the ordinary course of Providence, could befall it or any other place".

Curse or cursed? It certainly appears that neither the distillery, nor Talisker estate, lived up to MacAskill's expectations. In 1840 Hugh inherited estates on Mull, and with it Calfary Castle, where much of his efforts were to be directed. And despite the elegant and comfortable lifestyle that Talisker House offered, Hugh moved his family to Rudha an Dunain in nearby Braccadale in 1846. Three years later he gave up his lease on the Talisker lands. He gave up the distillery, managed by himself and his brother Kenneth with a brewer, Archibald Sinclair from Campbeltown, in 1848. The lease for the distillery and lands was transferred by the MacAskills to the North of Scotland Bank and the general management was passed over to the manager there, Jack Westland (Sinclair remained brewer until his death in the late 1860s). This suggests they may have been in financial difficulty at the time; when Kenneth MacAskill died in 1854 he was apparently the sole partner in the business, leaving stock in trade and distillery utensils to the value of £ 1374 3s 2d, and book debts worth £ 259 12s 8d. When Hugh MacAskill died in 1863 he left surprisingly little (only £ 2713 4s 1d), and had no interest in the distillery.

Donald MacLellan (sometimes MacLennan) purchased the Distillery from the North of Scotland Bank in 1857 for £ 500. He described himself as a farmer from Vatersay, Barra; he had married Normana Johanna McLeod Tolmie, a daughter of Hugh MacAskill. MacLellan spent 163 600 improving the distillery buildings and plant (it is possible that the distillery had been silent since Kenneth MacAskill's death in 1854), and in 1859 took over a 31 year lease for the lands of the distillery. Despite severe capital problems, caused by prolonged expensive (and ultimately unsuccessful) law suits involving the Barra property, he began distilling at harvest 1860. The result was "a heavy loss, which my Books will show, and which I account for in general from the circumstance that my want of capital made me unable to keep the Distillery in regular work..."; he was also forced to sell a large amount of whisky through an agent in Glasgow at a price considerably lower than that obtained through direct sale. He had also, since 1857, had to bear the cost of "wages to the persons looking after [the distillery]". On 5th November 1863, after only intermittent working of the distillery, MacLellan was sequestrated. The distillery was advertised for sale by MacLellan's trustees first at £ 700, then, in April 1864 at £ 500.

MacLellan's trustees appear to have employed him in

working the distillery on a limited scale after the bankruptcy.

By 1865 MacLellan had appointed John Anderson ("a

cantankerous gentleman") as agent for Talisker whisky in

Glasgow. In the following year Anderson took over the lease of

the distillery; in 1867 he purchased the distillery, which by

then was in a desperate state: "the thing was in ruins, and

all the dishes [stills?] useless". Anderson set to work

improving the buildings ("I think I have paid in extending

the distillery and renewing the vessels £ 5300"); he also

spent heavily obtaining stocks of Talisker on the private market.

"That money was expended in making the business what it is

now; in bringing out this old whisky, I established the character

of the whisky to the trade". Talisker was certainly

attracting a premium at this time, "not a gill" was

drunk on the island because "it was too dear".

MacLellan's trustees appear to have employed him in

working the distillery on a limited scale after the bankruptcy.

By 1865 MacLellan had appointed John Anderson ("a

cantankerous gentleman") as agent for Talisker whisky in

Glasgow. In the following year Anderson took over the lease of

the distillery; in 1867 he purchased the distillery, which by

then was in a desperate state: "the thing was in ruins, and

all the dishes [stills?] useless". Anderson set to work

improving the buildings ("I think I have paid in extending

the distillery and renewing the vessels £ 5300"); he also

spent heavily obtaining stocks of Talisker on the private market.

"That money was expended in making the business what it is

now; in bringing out this old whisky, I established the character

of the whisky to the trade". Talisker was certainly

attracting a premium at this time, "not a gill" was

drunk on the island because "it was too dear".

Anderson's optimism hid the fact that expenditure always ran ahead of income. Speculations in the purchase of English barley ("because for the last few years barley has been bad, and in 1877 and 1878 extra bad") led to further losses, which Anderson tried to overcome by using stocks of new whisky to clear his debts. Having increased the capacity of the distillery from around 20,000 gallons a year to 30,000 gallons he was confident of being able to clear debts by selling new whisky on the market. "There is not", he declared, "a whisky gets a better reputation on the market or brings a better price than Talisker whisky". Nonetheless things went from bad to worse; cheques were written without sufficient funds to cover them, and firms were invoiced for whisky that they did not receive, and that had not been made. Anderson's ability to keep track of his business and the activities of his clerk (who later absconded) were constrained by illness: "I may mention", he told his trustees, "that I cannot look into the books as I am so blind". When he was bankrupted in February 1879 Anderson put an optimistic value of £ 6500 on the distillery; his trustees valued it at only £ 2500.

Ironically, given one of MacAskill's principal reasons for establishing the distillery, Anderson's main liabilities were to corn factors and grain merchants. In less than fifty years the distillery had outgrown the rationale for its existence, and from then onwards could survive only on the basis of the quality of its spirit. More reasoned management, first from Alexander Grigor, a noted Speyside distiller who built markets for Talisker in Australia, New Zealand, Ceylon and South Africa; and then the ambition Thomas Mackenzie, whose Daluiane-Talisker Distilleries was a fledgling competitor to the Distillers Company, put Talisker on a sound and established footing.

As a consequence, it was one of the largest selling single whiskies in the country by the early part of this century, as both archives and the continued appearance of antique Talisker bottlings at whisky auction testify. Its reputation goes before it, and few serious malt whisky drinkers would be without a bottle of Talisker in their drinks cabinet. But who do they have to thank for this wonderful spirit of Skye, whose powerful nose and peppery palate can conjure up the essence of its birthplace in a way that few other whiskies can manage? The distillery's current owners? Or Mike Copeland, manager and fierce guardian of its heritage? Mackenzie, Grigor, Anderson, ManLennan et al, Hugh MacAskill and his brother? Or the hundreds of souls who toiled on the soil of the forefathers to scrape a meagre living in the nineteenth century, and to whose endeavours the landscape still pays eloquent testimony? Take a visit to Skye and decide for yourself.

Dr. Nicholas Morgan

Unless otherwise noted, all information in this site © The Scotch Malt Whisky Society, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1997.