Craigellachie

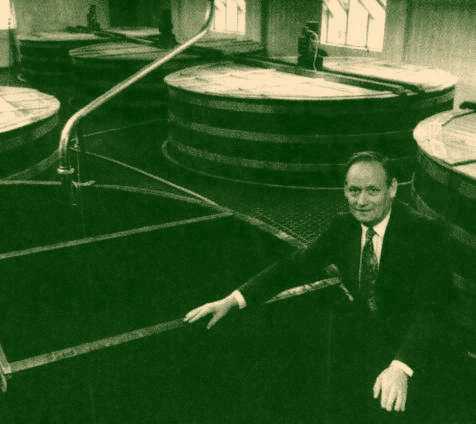

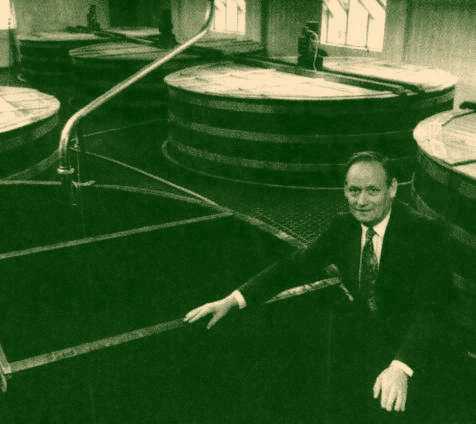

The man who built hisown washbacks

The headline above is an exaggeration of course:but that's headlines for you. Archie Ness, now manager atCraigellachie, didn't really build the distillery's washbackshimself. But he was certainly involved, back in 1964, when he wasa young member of staff and Craigellachie was being completelyrebuilt.

In the Sixties and Seventies, the Scotch whisky industry wasgoing through one of its periods of optimism. A few new maltdistilleries were being built, but large numbers of older plantswere being extended, and Craigellachie, Speyside, (dating from1891) was one of these. It was being "doubled up" fromone pair of stills to two and - with the exception of a fewbuildings like the traditional, long, low maturing warehouses,with their earthen floors - everything was to be torn down andreplaced.

This might have been sad,but it was also essential. The original buildings and layout hadbeen designed by a well-known 19th century distillery architect,Charles Doig of Elgin. But the coming of automation markedanother stage in the progress of whisky distilling - adevelopment that had raised a local, farm-based activity into aninternational business. The original buildings were no longeradequate.

This might have been sad,but it was also essential. The original buildings and layout hadbeen designed by a well-known 19th century distillery architect,Charles Doig of Elgin. But the coming of automation markedanother stage in the progress of whisky distilling - adevelopment that had raised a local, farm-based activity into aninternational business. The original buildings were no longeradequate.

Archie Ness, who had joined the distillery as a mashman a fewyears earlier, was able to watch this amazing transition takeplace. Incredibly, the rebuilding and re-equipping of thedistillery took only nine months. In particular, he remembers thebuilding of the eight wooden washbacks, the huge vessels in whichthe liquid is fermented, a job contracted to a firm of coopersfrom Glasgow.

This company brought to Craigellachie the thick, heavy stavesof Oregon pine which had already been shaped with plane andspokeshave, along with the massive iron hoops which would holdthe constructions together. The traditional wooden washback is,after all, not unlike a gigantic barrel standing on a broad base.

Archie Ness was one of the squad of distillery workers whohelped to assemble the washbacks under the supervision of theforeman cooper. With the wooden staves held in place, the metalhoops were forced downwards into position. This had to be doneevenly, by several men working from a platform round the washbackand striking the hoop in unison with heavy metal"pokers". It was painstaking - "and," saidArchie, "very hard work."

Thirty years on Archie Nessis back at Craigellachie Distillery, where he learned thedistiller's craft. The washbacks he helped build are still inbusiness, part of the process now delivering 47,000 litres AV ofwonderful Speyside malt each week. The learning of managementskills took him to other plants in the United Distillers group -Balmenach, Benrinnes, Dailuaine, Convalmore, Glenlossie,Speyburn, Imperial, Cardhu... In Speyside, you don't have totravel far to change your distillery.

Thirty years on Archie Nessis back at Craigellachie Distillery, where he learned thedistiller's craft. The washbacks he helped build are still inbusiness, part of the process now delivering 47,000 litres AV ofwonderful Speyside malt each week. The learning of managementskills took him to other plants in the United Distillers group -Balmenach, Benrinnes, Dailuaine, Convalmore, Glenlossie,Speyburn, Imperial, Cardhu... In Speyside, you don't have totravel far to change your distillery.

In Craigellachie, the distillery that bears the village's nameis known locally as the "White Horse distillery". Thisis because it's an important constituent in that blend which isnow the biggest-seller in Japan. But it has links that go back tothe island of Islay and the era of illicit distilling.

There, around 1740, a local entrepreneur ran ten"bothies" distilling whisky which, of course, was thendrunk unmatured. In the early 19th century, this skill waslegalised and developed into the distillery called Lagavulin("the hills in the hollow").

In 1878 a man called Peter J Mackie joined the company. He wasto become one of the great pioneering enthusiasts for Scotchwhisky - "Restless Peter", his staff called him - andhaving learned his craft on Islay he went into partnership in1888 to build Craigellachie. It was he who developed the WhiteHorse blend and took it to conquer world markets.

The site of Craigellachie Distillery was chosen for the usualsound reasons. There were good rail communications in those days.The buildings were erected beside the River Fiddich whichsupplied cooling-water and power: for until the 1964 rebuild, awater wheel drove the rummager in the wash still. And there isthe whisky-making water itself, taken from a spring on the nearbyhill of Little Conval and collected in the large Blue Hill damwhich is up to 40 feet deep. Craigellachie has never beentroubled by summer water shortages.

When Archie Ness first joined the distillery in 1962 it had upto 50 employees, compared with 10 today. It had its own floormaltings, kiln and small cooperage. He gained experience in everystage of production, but enjoyed most the pre-automation days inthe tun room. This is where the ground malted barley is mashedbefore the wort is sent on for fermentation.

It was an interesting,active job, constantly checking the temperature of the"liquor" and adjusting it manually with a cold-watervalve. In those days, water was applied to the ground malt fourtimes, at increasing temperatures, and drained off four times.The fourth water was basically to help the mashman push the spentflour towards a central sump, which he did from above with along-handled shovel. Nowadays, this job is done by a mechanicalplough and only three waters are applied.

It was an interesting,active job, constantly checking the temperature of the"liquor" and adjusting it manually with a cold-watervalve. In those days, water was applied to the ground malt fourtimes, at increasing temperatures, and drained off four times.The fourth water was basically to help the mashman push the spentflour towards a central sump, which he did from above with along-handled shovel. Nowadays, this job is done by a mechanicalplough and only three waters are applied.

The arithmetic of production is neatly organised, anddistiller's arithmetic has a marvellous logic. Each 5-day week,117 tonnes of malt is converted into 13 mashes, producing 26 runsof wash and 16 runs of spirit. What it doesn't produce is runs oftourists: Craigellachie Distillery, rebuilt for efficiency ratherthan charm, is not part of the whisky trail.

Every Friday the manager and his panel gather to nose somesamples of the week's production. This is a highly-specialisedform of nosing, because they are assessing very strong, unmaturedspirit: yet it is the ultimate form of quality control. At thisstage they look for a waxy sweetness, and any peatiness should bebarely discernible.

Less than a tenth of this noble stuff is bottled as a single,but it's given 14 years in the cask. That's some years longerthan the average Speyside. But its journey to your glass, viaArchie Ness's hand-built washbacks, is never less than anadventure.

Anthony Troon

If you have comments about thissite, please contact the webmaster. Unless otherwise noted, all information in this siteŠ The Scotch Malt Whisky Society, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1997.

This might have been sad,but it was also essential. The original buildings and layout hadbeen designed by a well-known 19th century distillery architect,Charles Doig of Elgin. But the coming of automation markedanother stage in the progress of whisky distilling - adevelopment that had raised a local, farm-based activity into aninternational business. The original buildings were no longeradequate.

This might have been sad,but it was also essential. The original buildings and layout hadbeen designed by a well-known 19th century distillery architect,Charles Doig of Elgin. But the coming of automation markedanother stage in the progress of whisky distilling - adevelopment that had raised a local, farm-based activity into aninternational business. The original buildings were no longeradequate.  Thirty years on Archie Nessis back at Craigellachie Distillery, where he learned thedistiller's craft. The washbacks he helped build are still inbusiness, part of the process now delivering 47,000 litres AV ofwonderful Speyside malt each week. The learning of managementskills took him to other plants in the United Distillers group -Balmenach, Benrinnes, Dailuaine, Convalmore, Glenlossie,Speyburn, Imperial, Cardhu... In Speyside, you don't have totravel far to change your distillery.

Thirty years on Archie Nessis back at Craigellachie Distillery, where he learned thedistiller's craft. The washbacks he helped build are still inbusiness, part of the process now delivering 47,000 litres AV ofwonderful Speyside malt each week. The learning of managementskills took him to other plants in the United Distillers group -Balmenach, Benrinnes, Dailuaine, Convalmore, Glenlossie,Speyburn, Imperial, Cardhu... In Speyside, you don't have totravel far to change your distillery.  It was an interesting,active job, constantly checking the temperature of the"liquor" and adjusting it manually with a cold-watervalve. In those days, water was applied to the ground malt fourtimes, at increasing temperatures, and drained off four times.The fourth water was basically to help the mashman push the spentflour towards a central sump, which he did from above with along-handled shovel. Nowadays, this job is done by a mechanicalplough and only three waters are applied.

It was an interesting,active job, constantly checking the temperature of the"liquor" and adjusting it manually with a cold-watervalve. In those days, water was applied to the ground malt fourtimes, at increasing temperatures, and drained off four times.The fourth water was basically to help the mashman push the spentflour towards a central sump, which he did from above with along-handled shovel. Nowadays, this job is done by a mechanicalplough and only three waters are applied.