Springbank

A Classic at the End ofthe Road

Anthony Troon visits Springbank, the greatCampbeltown survivor.

If you drive to Campbeltown, it always takes longer than youexpect. This is an immutable fact of life, like DNA or the tidetables. But if you're hunting down whisky, the tortuouslybeautiful route down to the end of the Kintyre peninsula is worthevery twist and turn.

While each malt distillery is different, surely none is moredifferent than Springbank. A tourist magazine would probably gushthat the past has stood still here: but it hasn't. It's just thatthe experience of the past has not been discarded, while anyso-called advances of the present and future are never adoptedfor simple reasons of economy and efficiency. The whisky comesfirst.

And the result is a whisky-and a distillery-unique for severalreasons. For Springbank does not make whisky the easy way (infact it makes two of only three surviving Campbeltown malts,Springbank and Longrow: the third, a rarity, is Glen Scotia).Once there were nearly 30 Campbeltowns, a reason why thisparticular style of whisky still has its own separateclassification. But it is no coincidence that the Springbank isstill revered as a great classic.

So let's ask how they do it. First youfind that the distillery, approached down a battered lane betweena depot selling concrete slabs and an evangelical church, is nota beauty designed for sightseer-orgasm. It's a working placewhere whisky has been distilled (legally) since 1828 and(illegally) from much earlier. Travelling abroad, to Italy or theGreek islands, you might appreciate best the places which haven'ttransformed themselves into fanciful tourist venues. Campbeltownitself, and the Springbank Distillery, have this quality ofintegrity.

So let's ask how they do it. First youfind that the distillery, approached down a battered lane betweena depot selling concrete slabs and an evangelical church, is nota beauty designed for sightseer-orgasm. It's a working placewhere whisky has been distilled (legally) since 1828 and(illegally) from much earlier. Travelling abroad, to Italy or theGreek islands, you might appreciate best the places which haven'ttransformed themselves into fanciful tourist venues. Campbeltownitself, and the Springbank Distillery, have this quality ofintegrity.

So to the whisky-making. Springbank is the only remainingScotch malt distillery which conducts the entire process itselfon a single site. It starts with barley, and it ends up withbottled whisky. Unusually, it germinates all of the barley ituses in floor maltings and dries it in its own kiln. The hugemajority of malt distillers now buy their raw materialready-prepared from industrial maltings. But Springbank's is thetraditional way, the labour-intensive way, the way you might havethought had disappeared: and it gives the distillery absolutecontrol over the quality of its whisky from start to finish.

Several things have made this possible. One is that thebusiness has remained in the hands of the same family sincepre-legal days. Another is that it doesn't keep the stillshammering away, day and night, in pursuit of some productivityrecord. It buys as much barley as it believes market conditionsindicate, malts it and kilns it-and only then, when the bins arestocked with up to 200 tonnes of malted barley, does it startdistilling. So in the average year, the stills will be operatingfor a total of only four months.

This is viable because the men who steepthe barley, germinate it on the malting floors and dry it in thekiln, then change jobs to operate the mash tun, the washbacks andthe stills. At the same time Springbank's tiny bottling plant-fedwith matured whisky from its own warehouses-works all year round.and something like 99 per cent of Springbank is bottles as asingle-malt, which is also very unusual.

This is viable because the men who steepthe barley, germinate it on the malting floors and dry it in thekiln, then change jobs to operate the mash tun, the washbacks andthe stills. At the same time Springbank's tiny bottling plant-fedwith matured whisky from its own warehouses-works all year round.and something like 99 per cent of Springbank is bottles as asingle-malt, which is also very unusual.

Director John McDougall, who has worked in distilling for 30years and says he's "one of a dying breed" (although helooks extremely healthy), told me that computer-managed microchipwhisky was an alien culture to Springbank. His whisky was made byreal people. In fact, Springbank has a permanent workforce of 24,more than double that of an obsessively modernised distillery.

But brewer Hector Gatt showed me how even on the traditionalmalting floors reintroduced two years ago, the advantages ofelectricity are not ignored. The sprouting barley is turned by amachine resembling a lawnmower. But when this breaks down, whichis not impossible, the men sigh, reach for the old wooden shovelswhich stand by in readiness against the wall, and laboriouslyturn the grain in the old way, by muscle-power.

There are changes also at the kiln, but nothing that you'dnotice. The peat used for drying (more for Longrow, less to makeSpringbank) is now brought in from Islay. Once the distillery hadits own local peat-banks, operated by two employees who wouldvanish up to the moor in April to cut and stack the aromaticfuel, and would rarely be seen again until October. Longrow, themore heavily-peated of these two malts, is quite a rarity andisn't made every year.

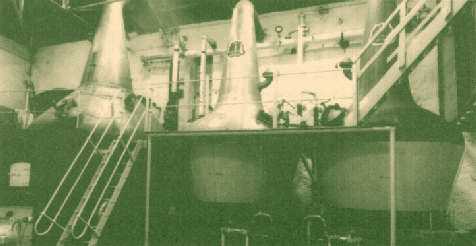

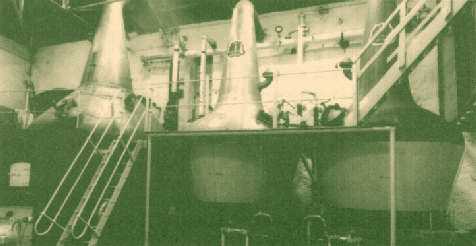

There's a row of three stills atSpringbank, but this doesn't mean that the whisky istriple-distilled. Oh no. Nothing is that simple here. Hector Gatttold me that in precise terms, it was distilled"two-and-a-half times". Because this sounds impossible,it requires some explanation.

There's a row of three stills atSpringbank, but this doesn't mean that the whisky istriple-distilled. Oh no. Nothing is that simple here. Hector Gatttold me that in precise terms, it was distilled"two-and-a-half times". Because this sounds impossible,it requires some explanation.

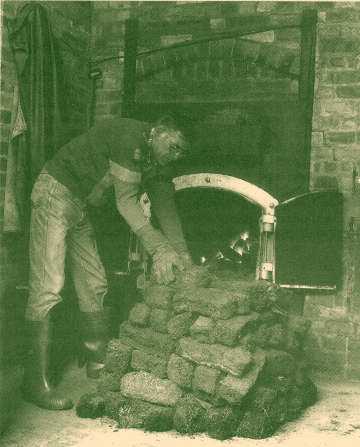

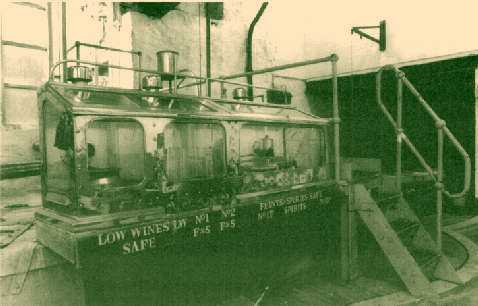

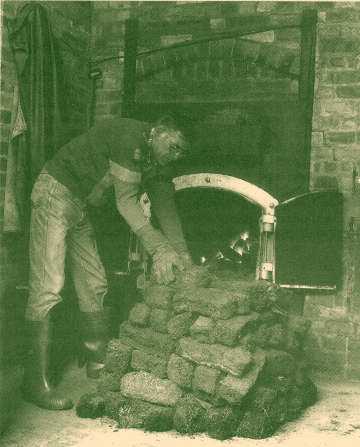

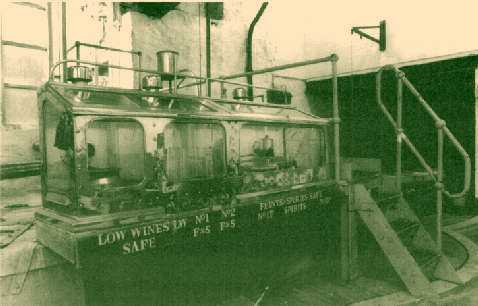

From any of the six larch-wood washbacks, the liquid goesfirst to the wash-still. Unusually (again) this is heated by alive flame from beneath, which requires a "rummager"-asort of copper chain-mail mat-to circulate inside and preventburning. From here, the low wines are treated again in the twospirit stills.

But one of the great characteristics of Springbank is its"body"-what some tasters would call its chewy quality.If the whisky was too strong in alcohol it would also be toolight. So the stillman will add a small quantity of low winesfrom the first distillation to the liquid which is to go throughthe third still. How much to add is a matter of experience andfine judgement. You couldn't program this into a computer.

Then it goes for the long sleep. Springbank is bottled at 12,15, 21, 25, and 30 years old. (Longrow, which isdouble-distilled, is usually bottled at 19 years.) So maybe, whenyou try Springbank, the great Campbeltown survivor, you nowunderstand why it's...rather different.

If you have comments about thissite, please contact the webmaster. Unless otherwise noted, all information in this siteŠ The Scotch Malt Whisky Society, Edinburgh, Scotland, 1997.

So let's ask how they do it. First youfind that the distillery, approached down a battered lane betweena depot selling concrete slabs and an evangelical church, is nota beauty designed for sightseer-orgasm. It's a working placewhere whisky has been distilled (legally) since 1828 and(illegally) from much earlier. Travelling abroad, to Italy or theGreek islands, you might appreciate best the places which haven'ttransformed themselves into fanciful tourist venues. Campbeltownitself, and the Springbank Distillery, have this quality ofintegrity.

So let's ask how they do it. First youfind that the distillery, approached down a battered lane betweena depot selling concrete slabs and an evangelical church, is nota beauty designed for sightseer-orgasm. It's a working placewhere whisky has been distilled (legally) since 1828 and(illegally) from much earlier. Travelling abroad, to Italy or theGreek islands, you might appreciate best the places which haven'ttransformed themselves into fanciful tourist venues. Campbeltownitself, and the Springbank Distillery, have this quality ofintegrity. This is viable because the men who steepthe barley, germinate it on the malting floors and dry it in thekiln, then change jobs to operate the mash tun, the washbacks andthe stills. At the same time Springbank's tiny bottling plant-fedwith matured whisky from its own warehouses-works all year round.and something like 99 per cent of Springbank is bottles as asingle-malt, which is also very unusual.

This is viable because the men who steepthe barley, germinate it on the malting floors and dry it in thekiln, then change jobs to operate the mash tun, the washbacks andthe stills. At the same time Springbank's tiny bottling plant-fedwith matured whisky from its own warehouses-works all year round.and something like 99 per cent of Springbank is bottles as asingle-malt, which is also very unusual. There's a row of three stills atSpringbank, but this doesn't mean that the whisky istriple-distilled. Oh no. Nothing is that simple here. Hector Gatttold me that in precise terms, it was distilled"two-and-a-half times". Because this sounds impossible,it requires some explanation.

There's a row of three stills atSpringbank, but this doesn't mean that the whisky istriple-distilled. Oh no. Nothing is that simple here. Hector Gatttold me that in precise terms, it was distilled"two-and-a-half times". Because this sounds impossible,it requires some explanation.